Deployment

We deployed to the Grosvenor Mountain region in the Trans-Antarctic Mountains. The actual landing area is a natural stretch of ice and snow near the Otway Massif. Apparently there is a sufficiently long enough stretch of icy snow to land the rather largish C-130 cargo plane. We loaded up from McMurdo and departed from William Field, referred to by the locals as Willie. This field is located on the more permanent McMurdo ice shelf and does not melt each summer like the sea ice runway located a stone throw away from McMurdo. The departure was uneventful, just like you want them to be.

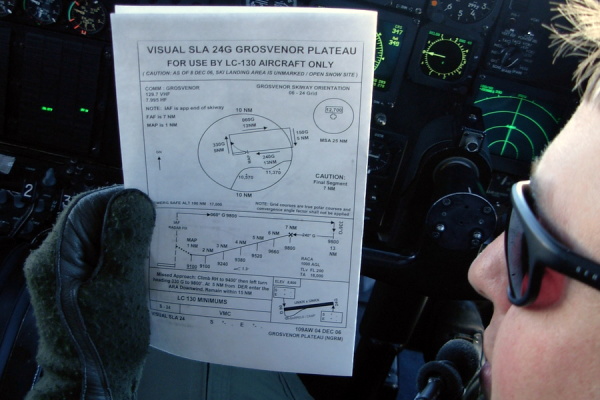

En-route to the Otway Massif, a trip to the flight deck was on the must do list. The pilot and navigator were looking at the approach plate for the Otway Massif which I found surprising that there was even one in existence. An approach plate is a sort of a localized map that tells a pilot important things about the place you are about to land. It has information like the direction of the runway, the length, the width, the altitude, a descent altitude profile so that you do not run into obstacles, and more. Their approach plate was this nearly blank piece of paper with a little line drawn showing the runway heading. The length was listed as “unknown”. So was the width. About the only number shown was the altitude. This map looked like it came from Lewis Carol’s “Hunting of the Snark” where the Captain, (in search of a Snark) was guided by a completely blank map. We made a low pass to give things a quick look-see before we went in for real. The landing was smooth and uneventful, just like you want them to be. Those C-130 boys from the New York Airguard know what they are doing.

After landing the first thing was to unload the palletized gear. Like some giant mechanized dog giving birth to a litter of puppies, the back ramp was lowered while still taxiing and out popped three pallets of gear, neatly spaced about 50 meters apart in the blowing snow.

Like storm troopers, our party came to life by jumping out and ran after the new born litter of puppies. The C-130 was obligated to stay until we had at least one tent set up, one stove burning, and radio contact with McMurdo. They did not turn off their engines. We gave them the thumbs up and they taxied away. Their departure was labored; taking an unknown distance down the unknown runway to get up to take off speed. Just when it looked like they were not gaining any more speed, rockets fixed to each side of the fuselage, fired and the C-130 lumbered into the air leaving us standing in a huge cloud of blowing snow and acrid rocket fumes. Ah, that smell is perfume to my nose.

Euphoria filled my being. There was a tinge of relief for now we knew the expedition was going to happen. I think this is a fear of any explorer, for reasons outside your control; your mission might be terminated before it begins. The acrid snow-mixed fumes were our seal of approval, the stamp that we were here and the exploration for meteorites can now begin.

I have had this feeling before. The departure of a drop off vehicle signals that there is no going back. This was the feeling when the Space Shuttle Endeavor pulled away from the International Space Station, leaving Expedition 6 to carry on. For missions of six weeks, or six months, the feelings are the same. Left standing in the middle of -20 degree nowhere, I was elated. After this reflective pause, perhaps a duration of 30 seconds, I went to work setting up camp with my team mates before we froze.

Next came the opposite flail of packing. As if attempting to reverse the ebbing tides of entropy and put all our gear back in the form from whence it came, we struggled with metal banding straps, and tie down winches with brittle wind chilled fingers. One of the first items to literally roll off the pallets was the snow mobiles. These things are like half mechanized dog half mechanized mule (especially when it comes time to start them). But once they stop blowing smoke, they are happy to do mountains of hard labor for you. We loaded up our Nansen sledges, wooden sledges that differ little from what folks had during the turn of last century. We set up a base camp for eight. All this time our snow mobiles were pulling back-breaking loads much what dogs would have done a century ago.

We set up a special tent reserved for the latrine. A tent, protecting one from the wind, is a nice feature to have considering the magnitude of the wind chill. Even the best laid plans sometimes turn up with small oversights, and such was the case for us. Within all the 8000 kilograms of gear, we could not find our toilet seat.

Sitting on the cold rime of a 5 gallon bucket was not our idea of a comfy private spell. My tent mate, a very crafty member of our team, came to the rescue. He fabricated a replacement seat from a piece of thick cardboard. As Jonathan Swift pointed out, necessity is the mother of invention.